Long winter expeditions present many challenges. Keeping clothing, sleeping bags and gear dry while underway are a very big concern when the option to come inside and dry out is not available for weeks at a time. Over the years I have employed many techniques to keep moisture to a minimum but none will be as effective as having a small wood-burning stove in the shelter.

Titanium Goat makes very lightweight (2 pounds), collapsible and efficient, cylinder, wood burning stoves. For our upcoming adventure to the arctic we will be carrying the 22-inch long version in our retrofitted pyramid shelter.

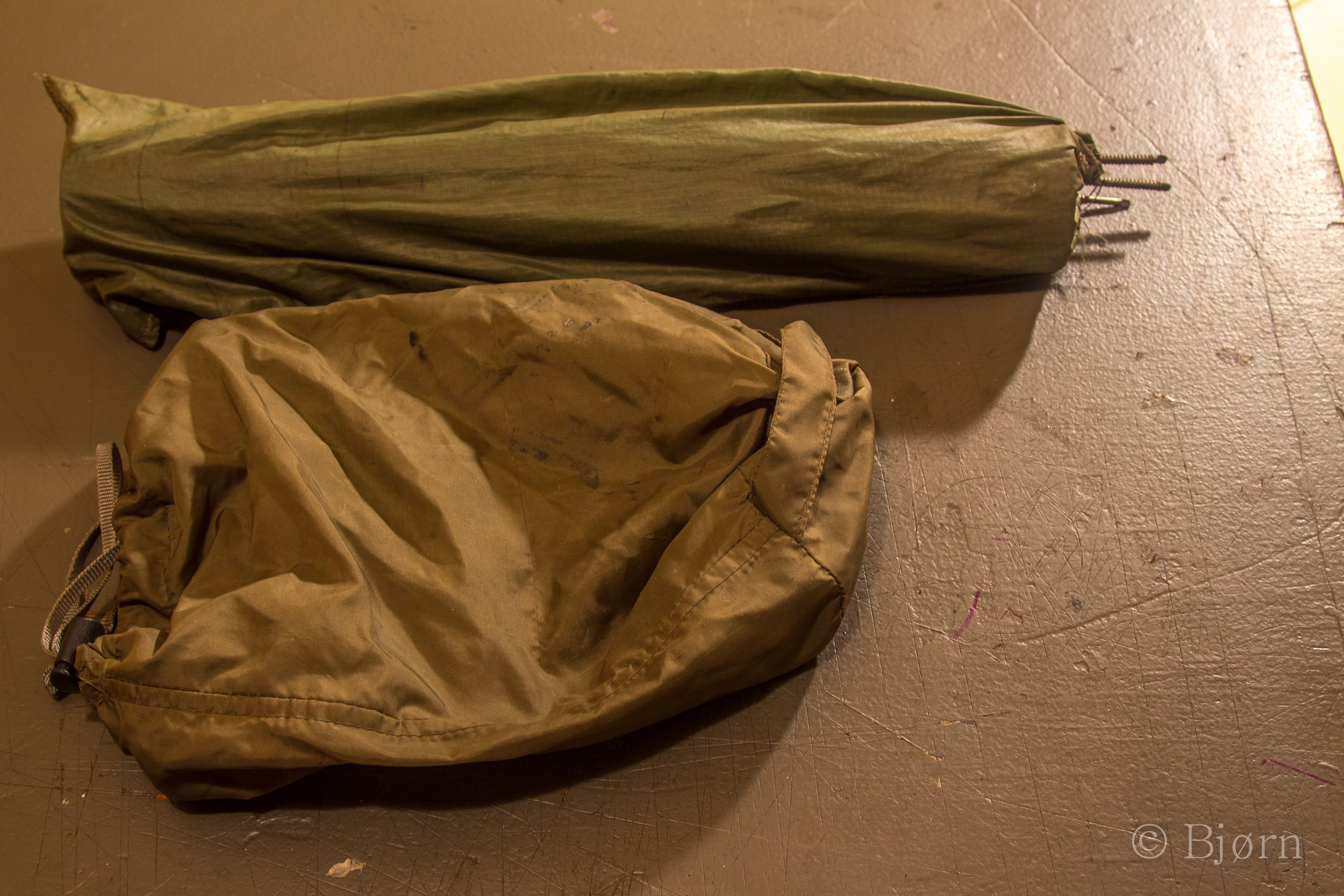

We decided to use Ground Truth Trekking’s old Mountain Laurel, silnylon, mid shelter, which we and Hig and Erin have used many times in the past. This may be the last hurrah for the shelter so we figured it would be a good one to experiment on. I also theorize that since much of the waterproof coating of this shelter has worn out, moisture may have a better chance of escaping through the fabric.

Our first task was deciding where in the shelter we wanted the stove and where the stovepipe should come out. We settled on having the stove in the middle with each of us sleeping on separate sides of the stove and center pole – allowing us equal access to heat. The stovepipe coming out of the upper, side triangle made the most sense.

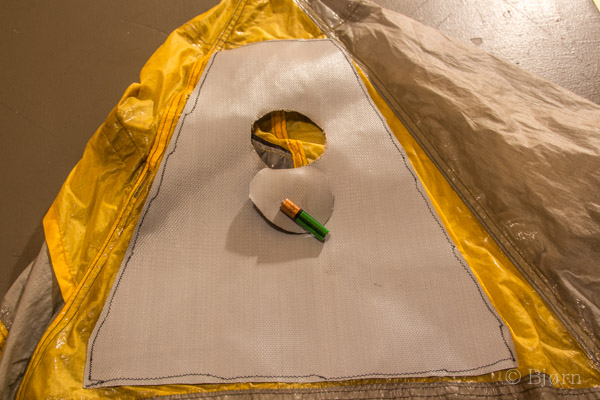

Once the location for the stovepipe was settled on I cut a piece of fireproof fabric into the triangle pattern of the shelter and cut out a hole for the pipe, leaving the circle un-cut at the bottom. Leaving the material hanging means we could cover the hole if we decide not to use the stove and it also acts as flashing for the stovepipe. Once the fireproof fabric was cut I pined it onto the shelter and sewed it on, using cotton thread and then cut out the silnylon.

With that, the retrofit was complete and it was time for a test. Kim and I loaded our bikes and headed into the Caribou Hills for an overnighter. For a single night out we couldn’t have asked for better weather to run our trial under – we experienced coldish (10º) temps in the night and woke to a snow storm.

After pitching the shelter we set up the stove together. Kim stayed inside and lit the fire while I harvested wood. When cutting wood, I was trying to anticipate how much we would need for both the evening and again in the morning. I ended up estimating fairly well but imagine on our trip we will require a little more as we will need to fill two 64oz thermoses, dinner, hot drinks and breakfast each day. It’s hard to quantify this into volume but I would say three full armloads of burning wood and a supply of kindling seems about right.

First impressions are all positive. The stove only has one setting – on. There is no damper and the door does not allow for closing down. In a shelter that does not retain heat this seems fine and melting snow into water means you want the most heat as possible. Stoking is fairly constant, at least with the dry spruce branches we were using. Moisture from our clothing was soon dissipating out the top vent and partially opened door. Within an hour we both had full mugs of hot chocolate, dinner and damp clothing was dry. Before bed we melted another 50 or so ounces of water and let the fire go out.

The next morning was warmer and snowing. The falling snow created a unique problem – it melted onto the shelter and once we let the fire go out this turned to ice. I believe the solution in this scenario will be to go out before the heat is gone and wipe or scrape the moisture from the shelter before it has a chance to freeze. Overall this is not too big of an issue as the next nights fire will dissipate the ice but it does make the shelter heavier and bulkier to carry.

Setting up the stove currently takes me around 5 minutes but I believe with familiarity we will be able to shave time.

Our model for the trip will be to alternate morning tasks. Every other morning one of us will wake up two or so hours before the other, light the fire and begin melting snow for the day’s water – a casual but persistent chore. This will also help dissipate moisture from sleeping bags and frost from the tent. We plan to alternate evening chores as well. One night one person cuts wood while the other prepares dinner and drinks. Both tasks keep you warm but the alternating keeps us fresh and in the past this kind of chore swapping has proved to be good for overall moral.

We have yet to experience strong winds with this setup but from what we have gleaned from others the stove seems to still work fine. The stovepipe outlet is well above the shelter and we saw no sign of rogue cinders coming back to melt holes. That said, I have little doubt that after six weeks on the trail our shelter will be pretty or hole free.

I also experimented with a lightweight bow saw that I made from a commercial blade and three pieces of thin, flat aluminum. Although the saw performed well enough for this trial run, I have my doubts. There is currently not enough tension on the blade and it wants to bend. We may end up bringing small folding handsaws. The jury is still in deliberation on this topic.

We are planning to rely solely on the wood stove for our trip and not bring a fuel stove. We will however leave my trusty MSR Whisper-Lite with Hig to send to us if need be. I imagine some camps will be harder than others to harvest enough wood but on all past trips I have found that as you go, people are generous with trail information. As is the case with all trips – you never know until you go.