It’s 3:00 AM. The moon is above my right shoulder casting a long shadow over the undulating snow. Riding my fat-bike, with my ruff pulled up and my hands tucked into large pogies, my shadow looks like some sort of half animal, half machine creature. My four friends and I are liberated from the trail, atop concrete-hard snow, picking any line we choose through the forests and meadows. I feel like an animal, like a wolf in a pack. We all hoot and holler with abandon.

Spring crust riding is one of the many great joys experienced by a year-round fat-biker. A year in the life of our particular fat-bike culture goes something like this:

June – August: Maintain and ride technical trails through local forests; half-day and full day beach rides (preferably on the most technically challenging terrain available); street sessions, e.g. curbs, benches, cylinders, steps, and other interesting urban lines and routes; several overnight trips (with or without packraft or partner); at least one big summer wilderness expedition with packraft and at least one partner.

September – November: Milk as much summer as you can and ride as much as you did until the season finally changes; take advantage of early freezing conditions before the first snow flies by riding up creeks, over bogs, and connecting backcountry lines that are otherwise too wet to ride in the summer or filled in with snow in winter; rally the homeys for a week-long friend’s trip, with or without packrafts (fall seems to be when everyone can most often pull away from busy schedules); take advantage of trails that become too overgrown with brush to be any fun in the summer; ride on and over as much hard, compact, frozen ground as possible.

December – February: Get your Black Metal fat-bike rides on; bundle up, strap on the headphones, blinker lights, headlights, and goggles; ride in every winter blizzard; remember how to stay warm, how to not sweat in your clothing, how to manage equipment in sub-freezing conditions; go camping on snowmachine trails every full moon; get strong.

March: Cut all ties and go on an expedition. March is the month—the siren’s call to the wilds. Accept no substitute. March is the time when winter starts to relax her grip a little and the daylight returns. In any northern region, snowmachiners and dog mushers feel the siren’s call, too. Learn where their trails go; find creative ways to cover vast amounts of country on these hard-packed and fleeting winter trails. Spend weeks—or an entire month—covering country on snow. Invest in good gear and make these expeditions as pleasant as possible; learn from each one and improve technique, means, and creative route-discovery every year.

April – May: Observe the snow and weather conditions and be ready to strike at the first hint that crust conditions are good to go. South facing slopes come first; eventually every aspect goes through the thaw-freeze cycle and the entire snowy world becomes a playground when it’s frozen. Wake up early and ride until the afternoon sun begins to thaw the snow again.

…and repeat.

Every season contains a few fleeting days or sometimes mere hours of euphoric perfection. There are the summer afternoons, for example, when the ground is dry, the bugs are down, the air still, and the dirty sweat on your forehead and arms feels like a well-earned callous; when your ride into the alpine leads you to a cold, inviting lake; when you drip dry on the soft heather and watch a cumulonimbus cloud billow over a mountain summit across the valley; when the hermit thrush sing their lovely call to one another through the dwarf hemlock forest and fill the air with well-being; when you don your grimy clothing and sweaty helmet and bomb back down the hill with the last of the golden light of day. Summer magic.

And in March when you find yourself far away from people and crowds; when the temperature is zero degrees and the air perfectly still; when the trail beneath your tires is rock hard and you have them pumped all the way up to 20 PSI; when an animal, maybe a coyote or an owl or a moose or a raven, crosses your path and you stop to watch it as it watches you; when you finally stop for the day, build a fire, cook a meal, share reflections, crawl into your warm sleeping bag, and go to sleep giddy with the insight that you get to do it all over again tomorrow. Winter magic.

In the spring, there is a lot of magic throughout northern regions. The world is returning from the long, dark, and cold slumber. With the additional light and warming air, life returns, animal and bird migrations begin, and sour moods get crowded out by the excitement of rebirth and renewal. For any outdoor enthusiast, spring is the time to strike, to forego sleep, responsibilities, and obligations. For fat-bikers, crust season is the magical and fleeting time period when everything else must be put on hold.

Crust snow occurs when the daytime temperatures are above freezing, and nighttime temperatures remain below freezing. The snow crystals metamorphose into round grains, commonly called corn snow, and become saturated and denser than winter snow. At night, this corn snow re-freezes and becomes nearly rock hard. At first, this only occurs on sunny, south facing slopes. As the season progresses, the entire snowpack, from bottom to top, undergoes this metamorphic transformation.

A lot of variables go into a good crust fat-biking season. How deep was the snowpack over the winter? What sorts of layers developed in the snowpack? Is the spring weather on a consistent trend or does it vacillate between spring and winter for weeks at a time? Is it going to rain all through April? Each of these considerations and more go into the perfect conditions. Often, entire years go by without this natural manifestation of ideal circumstances—all the more reason why it’s imperative to pounce when the stars do align.

Over the last decade, my crew and I have tried to be ready, willing, and able for this ephemeral springtime riding condition. We approach crust riding in one of two ways: aimless forays into the most interesting terrain we can find, where the objective is pure, giddy fun, or long rides to cross a lot of otherwise impossible-to-traverse terrain. If the season is particularly good, this can go on for weeks.

In general, we prefer to start our rides well before sunrise and, in some instances, we begin riding right after dark. It all comes down to when freezing starts to occur, how hard it freezes and, inversely, when it warms above freezing and how warm it gets. By obsessively observing the weather forecasts and spending time out in the country and on the snow, we begin, each spring, to develop a sense of what we can get away with.

For this type of riding, you can use almost any bike with plus or fat wheels. When the conditions are really good, even a mountain bike with two-inch tires can work. However, I always prefer a fat-bike with the fattest tires possible, and although studs aren’t required for traction on the snow, there are often a lot of ice conditions that appear this time of year. Super fat tires are insurance for when the conditions degrade and, with big, low-pressure tires, rolling over obstacles is both a cinch and a riot of a good time. A dropper seat post is not essential, but the joy of riding steep and technical crust lines with one can’t be overstated.

I also prefer to ride crust with the least gear and weight as possible. A water bottle, snack, a flask to share, a multi-tool, and a camera are all that typically make the cut for fun rides. This sort of cycling feels incredibly liberating and it’s ideal to approach the terrain unencumbered, able to give your all. The traction and terrain can feel similar to Moab’s slick rock and our riding attitude is similar to the culture found in that part of the world.

That said, overnight trips are fantastic during the crust season, too, assuming you entirely trust the conditions not to melt out from under you. Riding through the night under the stars and moon to a remote cabin over the snow on a route concocted entirely of your own imagination is the quintessential essence of what bikepacking can be. Loafing about, reading a book, napping, or chewing the fat while catching the afternoon rays and waiting for freeze up again add bliss to the complete experience.

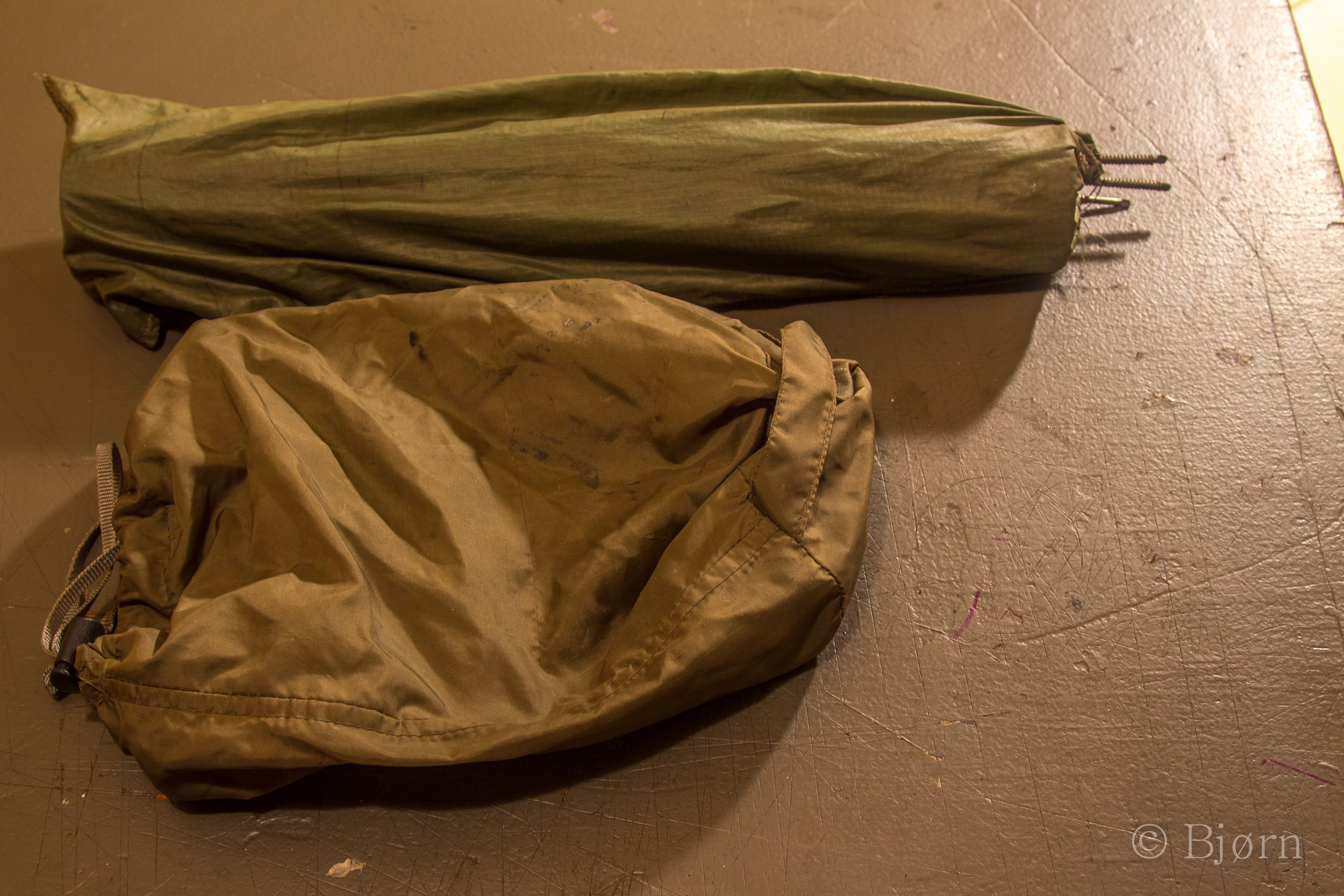

To feel as liberated as possible, I pare down my camping kit to the bare essentials. One puffy sweater, a hat, a lightweight summer sleeping bag, sunglasses, a Bic lighter, a titanium mug, a water bottle, snacks, instant coffee, multi-tool, pump, repair kit and, in our neck of the woods, a can of bear spray are essentially all that is required. Last year’s dry grass or spruce bows make fine sleeping pads and open fires do a remarkable job of bringing a cup of melted snow to boil for coffee. Another joy about this time of year is that many of the creeks begin to flow again and finding fresh drinking water is usually not a problem. There are typically many hours of the day and afternoon that are above freezing, and thus unrideable, so I typically splurge and bring a concentrated adult beverage (whiskey) and a small paperback book.

For the most part there are very few pitfalls or hazards associated with crust riding, but there are exceptions. Often, the surface snow can hide holes, crevasses, or open water. Riding over glaciers, fast moving water, or terrain so steep that you can’t see the entire runout need to be approached with caution. It’s only a minor inconvenience to have your bike punch through a big pocket of empty air when riding over a patch of buried willows; it’s quite another thing to fall 50 or more feet into a crevasse or an open hole above a river. Common sense and familiarity with terrain features should always accompany the savvy backcountry explorer.

Under the full moon, we instinctively begin playing a game of “follow the leader” through the forest. Whenever the leader’s line choice becomes too absurd and the terrain forces them to abandon it, another rider takes over. Up a spruce forest hillock, into a skate park dream gully, a log ride over a bent birch tree, a steep bomb-drop off a small cliff face to a beautiful transition, and finally into a patch of willows that offers no escape. “Your turn,” my buddy Daniel says. “Show us what you got!”

Shifted into low gear, I raise my dropper post and power up a steep hill. When the angle reaches an even steeper degree, it’s my strength that breaks my line, not the traction. Before losing my fight with gravity, I turn to the left and ride an upward angle just shallower than what my hill-facing pedal will strike, and then I turn hard to right. Climbing the mountain like a backcountry skier on skins, I reach the summit. From the top, several downhill lines present themselves. I’m overjoyed to be the leader for this run. I drop my saddle, give two hard cranks, lean back, and bomb down through the trees.

Eventually, our party remembers that dawn is approaching and we’d discussed a long ride to the village of Ninilchick. We give up the game and head down Deep Creek Valley, leaving the well-worn snowmachine trail untouched. Each person choosing their own high-speed line–bunny hopping over little mounds, banking turns in the creek bed, wheelie dropping over short drop-offs, but forward, always forward.

Hours later, we reach the parking lot where the evening before we’d delivered my truck to shuttle bikes and riders back home. The bags below our underslept eyes crease upward with fat grins and we awkwardly attempt a clumsy and fatigued group high five.

The next afternoon at 4:00 PM, my fiancé Kim and I finish our second cup of coffee and breakfast when both of our cell phones simultaneously chirp. The group text reads, “Crust ride?”