For the month of August I intend to only consume food from local sources. In this post I will attempt to lay out what I intend to eat and not eat, my feasting/fasting protocol, my inspirations, plus some resources for anyone else interested in taking on this nutritional challenge.

The genesis and inspiration for this challenge was born from the Bristol Bay village of Igiugig. In 2017 the entire community ate only local food for six weeks. Although I grew up in Alaska eating a lot of wild-harvested food, this will be the first time I have attempted to eat that exclusively.

Over the last year and a half, I have fallen down a rabbit hole of nutrition science and anthropology. My original impetus was simple: weight loss. I soon discovered, however, that the dietary thread I was tugging on was more holistic. By learning to become a fat burner and “metabolically flexible,” I soon began to experience a cascade of positive health improvements.

For example: my 20-year-plus eczema rash disappeared, achy joints and soreness have been nearly eradicated; I most often sleep a full night for the first time in my adult life; my mood and temperament have improved; I no longer suffer from low blood sugar crashes or feelings of “hangryness;” I have become insulin sensitive; my cognition, focus and ability to be present and in the moment are acute; most of the small skin tags I had have disappeared; chronic inflammation is a thing of the past; and the list goes on.

In order to feel so much better and healthier it might seem like I must have to consume a complicated diet, compounded with loads of supplements, perhaps even pharmaceuticals, with dogged persistence and loads of will power. Nothing could be further from the truth. My diet, fasting, exercise/recovery and hormetic stress practices are remarkably simple. This local food challenge will be a lucid progression of my current lifestyle.

There are many ways to approach the topic of Ketosis and even more ways to label it. I am a fan of calling the approach that I am pursuing an “ancestral diet.”

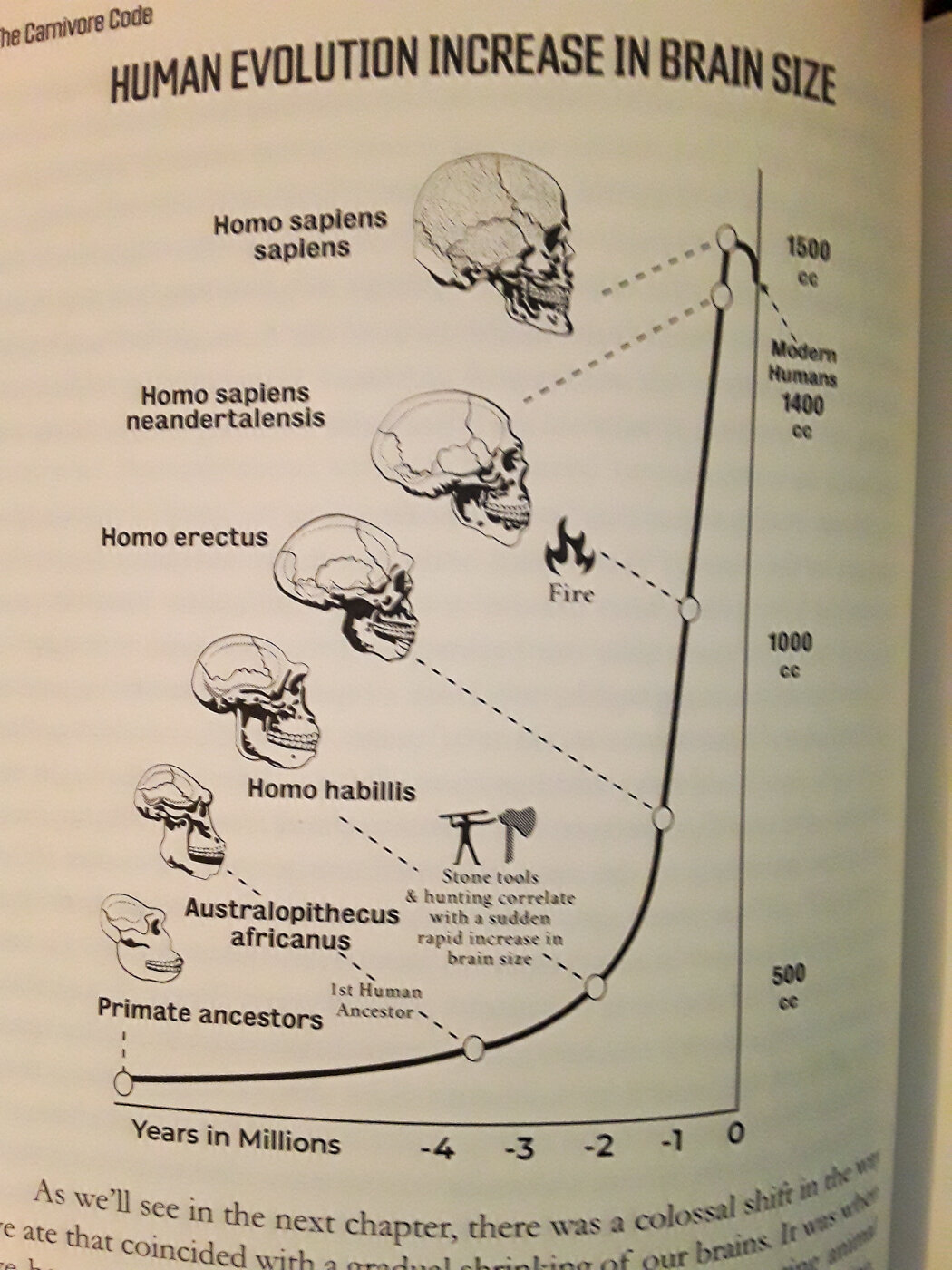

Because of climate change, roughly 2 million years ago, our hominid ancestors had to move out of the trees and onto the open prairies of eastern Africa. Brain size of these early humans (Homo habillis) was roughly 500cc. In this new and likely more intimidating environment, humans learned to scavenge and eventually hunt for their sustenance. It’s theorized that animal fat and protein propelled our evolution and brain size, which is now 1,400cc. (Homo sapiens brain size peaked at 1,500cc about 10,000 years ago and has been in decline since the advent of agriculture.)

From the book, Carnivore Code by MD. Paul Saladino.

There is no known, one size fits all, optimal human diet. Furthermore, there are as many opinions about proper diet as there are nutritionists, bloggers, bro-scientists, YouTubers, and dietitians. There are, however, some irrefutable physiological facts. Here are a few that I find fascinating and that I hitch the pony of my N-of-1 self-experimentation to: Ketosis is not so much a diet as it is a metabolic state. Either you are in it or you’re not. There is no such thing as an essential* carbohydrate. Fasting is as natural and as restorative to humankind as breathing. Wild-caught Alaskan fish and game is some of the most nutrient dense and healthy food in the world. Exercise is crucial for health and well-being; ancestral exercise is optimal -- as much aerobic as possible (able to get enough air while doing it that you can hold a conversation), periodically lift heavy things, and periodically employ high intensity intervals training sessions. Persistent and chronic stress will kill you prematurely; hormetic stress will make you live longer and more optimal. Rest and recovery are as important as regular exercise. Metabolic flexibility is as remarkable as it is liberating.

It is fair to say that what works for me may not work for anyone else, but anyone who wishes to live a long, healthy life should consider ditching sugar, refined grains, hyper-processed “food” (everything from the middle isles of the store), and industrial seed oils. With that aside, the spectrum for discovering what dietary protocol works best for any individual is vast.

One key principle for me is that the food I eat is satisfying, which is to say that it does not feel like a “diet” or that I am depriving myself in order to be healthier. Every bite of food that I consume these days is immensely gratifying. In the moment of consumption, I don’t care if the food I am ingesting is helping restore my hormones into balance, that I am replenishing my liver and muscle glycogen through gluconeogenesis, or that I am balancing my Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio. All I care about is that it’s delicious, and nothing is as tasty to my pallet as Alaskan fish and game.

Another important consideration for me is that the food that I eat is ecologically sustainable. Alaskans should take immense pride in the fact that we still have mostly intact ecosystems that support some of the world’s most nutritious fish, fowl and game. To eat only local food would be more challenging in other states or provinces that have traded their renewable resources for short-term profits.

For my own N-of-1 sake, I am excited to see if there are any noticeable improvements in my health over the next month. I also want to deepen my intuition for how much food I actually need to put away every season, as well as connect with and learn from other people around Alaska and beyond who are undergoing the challenge to enrich our connection to the land, sea, and water that supports this nutrition and our well-being.

In order to keep this one month challenge reasonable, I plan to eat a very simple, high fat diet and I will likely only eat one big meal a day, or two at the most. It took some time and willpower, but I have kicked my sugar/carbohydrate addiction and have become a fat-burner/metabolically flexible. This metabolic state allows me to fast for 24 or more hours with ease and with plenty of stable energy. Anyone can become metabolically flexible. By all accounts, including my own, once this transition has occurred, it feels like you have a new super power.

Our Alaskan wild salmon are the envy of the world; our moose and caribou outshine even the finest grass-fed/grass-finished pastured beef; our soil is rich and our water unspoiled. These are sacred. The local food challenge is a way to remember.

In later updates and posts I will share my meal plans, my macronutrient ratios and more.

*An essential nutrient is a nutrient required for normal body functioning that can not be synthesized by the body. Categories of essential nutrient include vitamins, dietary minerals, essential fatty acids and essential amino acids.